(Originally published at D/Visible Magazine, this is Part Five in the ongoing essay series on live art, Painting While Dancing.)

Setting up an easel at concerts and inviting people to watch as you paint (or sculpt, or arrange flowers, or whatever art form you do that is more typically hidden from prospective audiences) is…different.

Most art forms are kept hidden in the studio until some dramatic Moment Of Unveiling. Instead, the transparency of performance makes this strange behavior distinct enough to deserve a name that will set it apart in people’s minds from the rituals and religions of conventional studio art. Process becomes an obvious, living part of the piece. Journey and destination take on new meanings. Since music, dance, and theater evolved in context as public entertainment or ritual, they belong in a separate category (especially those composed beforehand). In fact, it is the very change of context that makes something like performance painting strange in the first place.

People have taken to calling this kind of thing “live art.” It is probably better than nothing; but insofar as it is used to realistically distinguish one kind of creative expression from the rest, “live art” is nonsense.

For one thing, all artwork is part of what biologist Richard Dawkins calls “the extended phenotype.” Just as the spider’s web is as much an extension of its own genetic code as the spider itself, the artifacts and implements of art are part of the artist’s own breathing body. (It is, after all, called “a body of work.” If you think this kind of literalism is a stretch, try taking scissors to someone’s latest opus. They’ll act like you’re about to amputate a limb. As for tools, recent neurological research demonstrates that after just a few minutes using a hammer, our brains remap our bodies to include it as part of our arm. The brush or violin or laptop is, in some unutterably strange but natural way and in spite of modernist notions to the contrary, a cherished organ of the artist. Humans are cybernetic creatures, self-modification ubiquitous among us.

As linguistic beings, we are constantly in the game of renegotiating this self/other boundary. We supplement ourselves with expression-augmenting toys; hang names and titles on them like we are decorating a Christmas tree; plant flags in the ancient, wild terrain of the body and claim it for the egoic waking state (although clearly selves change over time…we hang onto our story of continuity in spite of overwhelming evidence to the contrary).

Take this other-as-self line of reasoning far enough, though, and you end up in a world that is entirely alive and looking back at you from everything. All perception is focused by history, all thought is woven of language, and we all only see mind in all directions, only feel mind in all directions. It isn’t the best argument for why “live art” is a nonsense term.

Therefore also consider that we are all witness to, and the declared actor responsible for, many of the things we do. Not even most, but many, and motivation is a very real dimension of any creative act. Who are we trying to talk to? In the act of art, especially in the flow states common to total participation, a deeper eye is watching. Audience feedback still informs the piece, because every work of art is a performance, even if it is for an audience of one. Even if we think we are only playing to satisfy the compulsions of our chattering minds, awareness itself is the substance of our perceptions and the basis of even our lowliest attempts.

Some people get religious about it, building churches and the like. Throughout history, it seems, the greatest works are those made from an awareness of the wider mind that watches. In that kind of harmonious duality, the uncharacterizable observer can not really be called “alive,” and so the job goes to the artwork.

Again, that kind of absolute statement gets us nowhere; so let’s add a dimension.

Every work of art – not just music and dance, but also architecture, painting, poetry, sushi – is created in and through time, something that grows and changes, moves and breathes on its journey to completion. No matter how well planned, all art has improvisation at its heart, and is thereby connected to the same creative force pulsing through the quivering leaves and darting fish. The product is inextricable from the process. Some art forms emphasize this; Zen calligraphy and expressionist paintings are especially transparent about it.

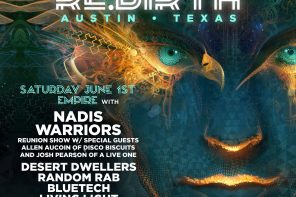

Among so-called “live artists,” however, the evolutionary nature of art is key. For those who make visual art a public performance, the focus is on reflecting, not necessarily capturing, the energies of a specific moment. Live painter Norton Wisdom, who has been in the game longer than anyone, works on a plastic sheet he wipes clean after every show. Others continually paint over the same canvases. Just like more conventionally-defined life forms, some paintings leave fossils and others vanish into the stream of time.

(For more on the intersections of art and science, visit MichaelGarfield.blogspot.com.)